Please note: the SAGEX programme was completed in August 2022, and this website is no longer being updated.

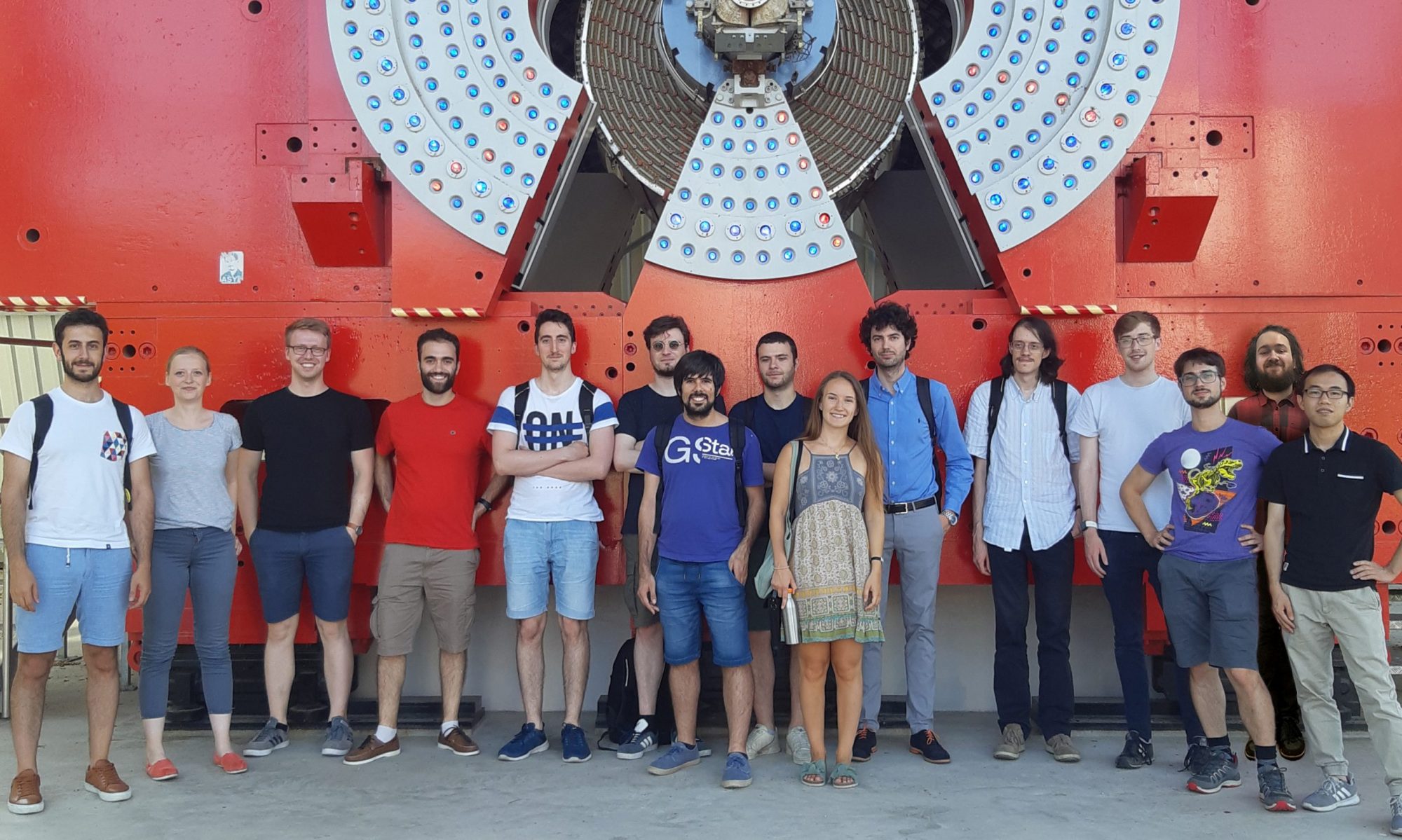

SAGEX is an Innovative Training Network funded by the European Union to train the next generation of world-leading scientists in the field of scattering amplitudes.

Take a look at the online exhibition ‘SAGEX – at the Frontiers of Physics‘, created by the SAGEX ESRs, about their work in scattering amplitudes. Explore the web app, which allows you to experience the wonderful world of quantum particles, from basic concepts to cutting-edge ideas, through short videos, games, and other interactive elements.

Watch the film made by the ESRs ‘Doing a PhD in Physics’ here!